by George Steele

2016

The technology currently exists to flip the way we practice academic advising. A "flipped advising" approach is similar to a flipped-classroom approach. The latter was described by Tucker (2013), "The core idea is to flip the common instructional approach: With teacher-created videos and interactive lessons, instruction that used to occur in class is now accessed at home, in advance of class," (p. 82).

The easiest way to start this transformation is for advisors to use their institution's learning management system (LMS) to create modules and exercises that support the advising process. While there are many vendors who make LMS, most share characteristics of being able to organize content and multimedia resources into modules, tools to evaluate student learning, and communication tools that permit interactions between instructors and students as well as between students.

For example, advisors who work with undecided students may find Gordon's (1992) curriculum a wonderful illustration of how modules can be organized (p. 75). Each of Gordon's modules of self-assessment, educational planning, career planning, and decision-making are easily creatable in the digital environments provided by an LMS. Not only can content be created and organized, but, equally important, students can be evaluated on what they have learned by using the LMS evaluation tools. With the use of LMS communication tools, advisors can monitor or assign students appropriate exercises from the modules. The flipped advising process has students complete assigned exercises prior to the advising session. These exercises could use rich multimedia resources created by the advisor or an advising team that can be organized in the LMS, as modules, and align with designated learning outcomes. The critical advantage of this approach is to have students complete modules prior to meeting with an advisor, so time in the advising session can be focused on higher-order cognitive and affective domain questions derived from the work the student has completed prior to the session. The goal of ensuring advising dialogue between the advisor and advisee would be to help students make connections and develop understanding between their completed exercises, found in the modules, and their academic and career planning process. Such an approach for advising would reflect the core idea of the flipped classroom approach.

Creating Modules for Deeper Learning

Examining how to create a flipped advising session provides subtle examples of the advantages of this approach. Gordon's module for self-assessment provides a useful illustration. Many examples of useful resources and activities were presented in the previous section of this tutorial in the module Self-Assessment. For content, an advisor could use any of the O*Net (a U.S. Department of Labor website that includes descriptions of the world of work) interests, ability, or career value inventories shown in this module. Since these interactive inventories are web-based, students would have easy access to them. By using the LMS quiz tools, students could record their results to these self-assessment inventories. The LMS also offers the ability for advisors to record brief videos that could address topics such as the purpose of the exercise, key considerations students should be aware of while taking the inventories, and the process for completing the exercise. To assist in the learning process, the LMS quiz function, designed for a written response, can ask higher-order cognitive and affective questions and record students' responses (Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956). The type of questions to encourage students' reflection through written responses could be as follows.

- Do you feel comfortable with the results of your self-assessment inventories for interests, abilities, and career values? If “yes,” why? If “no,” why not?

- What relationship do you see with the results of your self-assessment inventories for interests, abilities, and career values?

- Do you see any relationship between the results of your self-assessment inventories for interests, abilities, and career values and some of the academic programs you are considering? Some possible career paths?

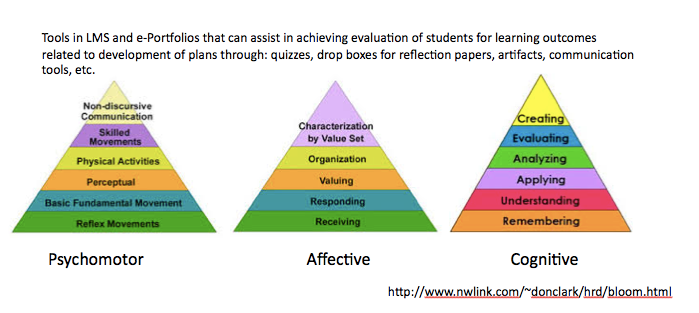

Clarifying and higher-order questions during the advisor and advisor-advisee sessions are critical to helping students see the relationships between elements of their planning and developing a deeper understanding of it. The three Bloom's taxonomies are shown below with their component sections that can help advisors guide higher-order questions in each of the taxonomies.

Image 1. Bloom’s taxonomies of learning domains. From Clark, D. (2015).

The flipped model puts more of the responsibility for learning on the shoulders of students while giving them greater impetus to experiment (Educause, 2012, p. 2). In a flipped advising approach, the student should come better prepared to the advising session. This goal is to diminish the need of the advisor to use the advising session as a means of primarily presenting information to students. Instead, the focus of the session shifts to helping students make meaning of their academic and career planning. Thus precious time is freed to help students with their planning and decision-making.

Gordon’s Advising Session

As Gordon (1992) has pointed out, the primary purpose of the advising session is to help develop the advisor and advisee relationship so as to help the student identify and work through issues and challenges. The student uses interaction with the advisor and appropriate resources to make sound decisions as a part of their planning process. Gordon (1992) suggested the following components for an advising session, whether it was for 20 minutes or an hour (p. 53). The sequence is meant to be a guide, not an inflexible process that needs to be unflinchingly adhered to by advisors.

Opening the interview

- Opening question or lead, for example, "how can I help you?"

- Obtain student 's folder or digital advising notes so relevant information is available during the interview and note can be added later

- Openness, interest, concentrated attention are conveyed

Identifying the problem

- Ask to state the problem; help student articulate need

- Help student articulates all relevant facts; gather as much information as needed to clarify the situation to you and students.

- Is presenting a problem covering the real problem? Ask probing questions, open-ended questions

- Restate the problem in student's words; give the student a chance to clarify, elaborate, or correct your interpretation

Identifying possible solutions

- Ask the student for his or her ideas for solving the problem

- Help student generate additional or alternative solutions

- What, how, when, who will solve the problem?

- What resources are needed?

Discuss implications for each solution if two or more are identified

- Taking action on the solutions

- What specific action steps need to be taken? Id procedure, information, or referral needed?

- In what order do action steps need to be taken?

- In what time frame do they need to be taken?

- What follow-up is needed? By student? By advisor?

Summarizing the transactions

- Review what has transpired, including restating action steps

- Encourage future contact: make a definitive appointment time if referral or assignment has been made

- Summarize what has taken place in student's folder or digital advising notes including follow-up steps or assignments if made (Gordon, 1992, p. 53)

Re-configuring the Advising Session

In a flipped advising approach, using an LMS would add an asynchronous layer to the synchronous session. Some of these advantages of adding this asynchronous layer are presented below for each step of Gordon’s advising session outline.

Opening the interview. The opening session becomes less of a re-introduction between episodic advising sessions and more of a continued conversation through the use of the communication tools found within the LMS. The use of email, chat, and posts are all ways for the advisor and advise to maintain a dialogue as the student works through the modules. Because these communication channels are secure, the advisor can carry on a more personal exchange with a student. Students can also be formed into groups to work collaboratively. In addition, an advisor could supplement communication channels by using secure video-conferencing too. This would enable the advisor to share a screen with the student and help him/her navigate problematic sections of the modules.

Identifying the problem. Because the work the student is doing in the module is stored in the LMS, advisors are able to reference back to sections where a student might have had difficulty. This would include examples such as quizzes about content, assignments that have been submitted, or sections of the module not address by the student. The critical point is that the intellectual work that the student has done can be reviewed by the advisor either before or during the session. This means the conversation is much more grounded in the actual work of the student.

Identifying possible solutions. Student work is digitally available to the advisor and advisee, thus providing a rich source for dialogue. By comparing and contrasting the student’s efforts in the LMS, an advisor can ask the student higher-order and probing questions to help the student make connections and see relationships perhaps previously not considered. In regards to Gordon’s curriculum, this could be asking students to explain the relationship between identified interests, abilities, and values, addressed by the student in the self-assessment modules, with tentatively identified academic programs and career directions, found in those respective modules. From these types of conversations, an advisor can suggest possible “next steps” to an advisee as new challenges arise with referrals to existing resources in LMS or on campus. This would also be an opportunity to refer students to the use of other technologies used on campus, such as degree audits or registration.

Discuss implications for each solution if two or more are identified. Once possible “next steps” are identified, the advisors and advisee can discuss priorities for future action. To help the student internalize this process, an advisor could have the student write a brief statement, as an assignment, within the LMS. It is also possible in most LMS to leave brief verbal messages. Either approach would leave a digital document for the student’s record.

Summarizing the transactions. With the digital record of the student’s planning and communication interactions with his/her advisor being stored in the LMS, an advisor can better monitor if the student is following up on the summarized transactions.

While many considerations need to be undertaken to implement a flipped advising approach, there are two that are critical issues. The first is the need to reach out to various campus constituencies to help develop the modules. For example, a team comprised of counseling services and career advising along with academic advising might be needed to create Gordon’s four modules. The second critical consideration is working with campus IT and learning services so that advisors’ caseloads of students are properly loaded within the LMS. There also must be a recognition that there is a need for technical flexibility. Advisors’ caseloads might also need to be configured to permit monitoring of students’ work within modules (e.g., group activities, career exploration, or early experience courses). For, in the end, flipping advising is potentially a great disruptor of how we conduct advising, rather than adding technology to existing bureaucratic systems.

Additional Advantages of Adopting a Flipped-Advising Approach

There are several advantages to adopting a flipped advising approach that extends instructional capabilities within the teaching and learning advising approach. Some of these includes:

- Advisors can tailor future student planning in a manner that is appropriate to students’ needs. While in a course or workshop, the structure of the curriculum often must be adhered to for the administrative purpose of dealing with larger groups; in the advising session, an advisor may want to skip around to a different exercise found in different modules of Gordon’s curriculum to help a student with a specific issue and solutions.

- The use of the LMS makes it flexible in a face-to-face advising session or ones conducted as a video conference or teleconference.

- The relationship between the use of an LMS and e-Portfolio, simply put, is that students engage in setting goals and planning in the LMS while showing their goals and accomplishments, as artifacts, in an e-Portfolio (e-folio Minnesota Showcase, n.d.).

- Since students’ works are recorded digitally, these can serve in aggregate for program assessment so that how students perform against specific program learning outcomes can be more easily tracked. This is the basis for program assessment (Robbins and Zarges, 2011; Steele, 2015 & 2016). This also provides the opportunity to capture a wider array of students’ generated data for different types of learning outcomes. In short, behavioral, cognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning outcomes can be assessed.

- Modules can be expanded beyond those identified by Gordon to include topic areas such as institutional policies and procedures; avoiding committing plagiarism; how to use campus technologies such as degree audits, e-portfolios, and course registration; developing good study habits; steps students can take to begin a thesis or dissertation; developing leadership skills; and financial aid and financial planning.

- The costs for pursuing creating a flipped advising approach can be much less than purchasing a proprietary software solution since most institutions have an LMS (Dahlstrom, Brooks, & Bichsel, 2014) and many of the internet resources would be locally developed or free, such as the O*Net resources previously mentioned.

Conclusion

Creating a flipped advising approach creates many positive outcomes. For students, it provides, at a minimum, a structured environment in which to develop their academic and career plans based on reliable information and resources selected by their advisors. For advisors, the flipped advising approach provides a means of extending the advising session to a 24/7 model while providing communication and evaluation tools to assist in tracking their students’ planning process. The flipped advising approach also supports advising as a teaching and learning activity. Finally, the flipped advising approach provides rich sources of data advisors can use for program assessment. These rich sources of data can help advance advising as teaching approach because they help advisors determine how various types of learning might influence student success and completion.

Citation for this article: Steele, G. E. (2016). Creating a flipped advising approach. NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources. Retrieved from https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Creating-a-Flipped-Advising-Approach.aspx (Links to an external site.)

References

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.). Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York, NY: David McKay Co Inc.

Clark, D. (2015). Bloom’s taxonomy of learning domains. Retrieved from http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html (Links to an external site.)

Dahlstrom, E., Brooks, D. C., & Bichsel, J. (2014). The current ecosystem of learning management systems in higher education. Retrieved from https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ers1414.pdf (Links to an external site.)

EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative. (2012). 7 things you should know about…Flipped classroom. Retrieved from https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/eli7081.pdf (Links to an external site.)

EFolioMinnesota Showcase. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://efoliomn.com/showcase (Links to an external site.)

Gordon, V. N. (1992). Handbook of academic advising. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Robbins, R. & Zarges, K. M. (2011). Assessment of academic advising: A summary of the process. NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources. Retrieved from http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Assessment-of-academic-advising.aspx (Links to an external site.)

Steele, G. (2016). Don’t pass on iPASS: Recalibrate it for teaching and learning. NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources. Retrieved from https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Dont-Pass-on-iPASS-Re-Calibrate-it-for-Teaching-and-Learning-a6416.aspx (Links to an external site.)

Steele, G. (2015). Using technology for intentional student evaluation and program assessment. NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources. Retrieved from http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Using-Technology-for-Evaluation-and-Assessment.aspx

Tucker, B. (2012, Winter). The Flipped classroom: Instruction at home frees class time for learning. Education Next, 82-83. Retrieved from http://educationnext.org/files/ednext_20121_BTucker.pdf