Authored by Julianne Messia

2010

The impact of and involvement in an academic advising program reaches far beyond the relationship between an advisor and student advisee. Academic advising does not occur in a vacuum; indeed, “ effective academic advising requires coordination and collaboration among units across campus that provide student support and services” (italics added; Robbins, 2009, slide 11). Advising, while necessarily linked with providers and support services, has the potential to impact and be impacted by other constituents of the college community, both internal and external. These influences, decision-makers, providers, and “clients” i.e.,students, their future employers, and the community, are implicated at various points throughout the administration of an academic advising program. This article presents a framework by which various stakeholders of academic advising can be identified, categorized, and become involved in the academic advising program. Strategies for involving all stakeholders, supporters, and detractors at varying degrees of program implementation are provided. It is important to note that not all stakeholders will or should be involved at every step of planning, implementation, and assessment.

Identifying Stakeholders

Whether providing advisors with accurate degree completion checklists, promoting the benefits of advising at new student orientation, or making the case for more resources, the key functions of an advising program do not occur independent of campus constituents. Identifying stakeholders allows administrators to appreciate and understand the unique campus environment in which advising operates. With this information, the advising administrator can begin to assess opinions of stakeholders and identify potential supporters and detractors. Furthermore, an advising administrator with a complete stakeholder analysis at hand can clearly distinguish who can, does, and should

- make decisions about advising;

- outline effective communication pathways;

- assess and distribute advising workload in special projects or committees;

- identify relevant parties in assessment and strategic planning.

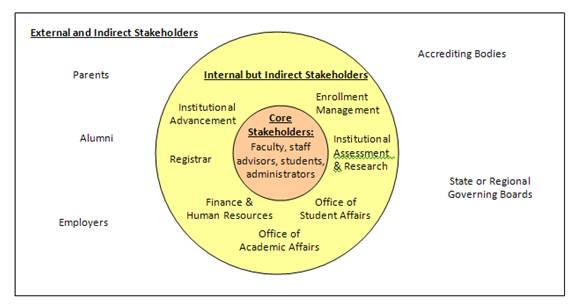

A complete stakeholder analysis, therefore, not only names the stakeholders but accurately characterizes each stakeholder’s power and influence. Harney (2008) identified advising stakeholders as being either internal or external constituents. Stakeholders belong in one of three distinct classifications: (1) internal core stakeholders, (2) internal but indirect stakeholders, and (3) external and indirect stakeholders. The chart below (Figure 1) depicts these groups in a diagram representing their various levels of input, influence, and involvement; the closer a group is to the “core” the more investment and weight that group has in advising. The groups utilized in this specific example assume a shared model of advising (both faculty and advising professionals have advising responsibilities). As each institution has its own unique culture and advising model, the chart should be adapted for any program or institution. For instance, an institution with a centralized advising model may list faculty as Internal but Indirect Stakeholders as they do not provide or administer advising directly.

Figure 1. Academic advising stakeholder framework.

Core Stakeholders: At the very center of the diagram is the “core” of principle players in academic advising. This constitutes students, the professional staff of advisors (including the director), faculty who serve as advisors, and direct line administrators e.g., department chairs, an associate dean for students, or provost. These individuals are directly involved in providing academic advising, enforcing academic regulations or enforcing advising policies and procedures.

Internal but Indirect Stakeholders: Internal stakeholders who are not directly involved with academic advising but can be allies in accomplishing programmatic goals, evaluating the program, and planning for the future are included as indirect stakeholders. In this example, departments such as the registrar, institutional advancement (fundraising), institutional assessment and research, finance and human resources (for advocating for new staff), and enrollment management (admissions and financial aid) are listed. Each of these departments would have a relationship with students that could be further enhanced if advisors work in tandem with office personnel. Building these internal connections helps centralize advising as part of the student learning experience at the institution at large (Vallandingham, 2008).

External and Indirect Stakeholders: Outside members of the broader institutional community and those who may influence the institution without directly participating in the advising process are external stakeholders. This can include parents, alumni, employers of our students, and accrediting bodies of the institution. In some cases, taxpayers, local K-12 schools, and institutions with transfer articulation agreements may also be included in this schema (Harney, 2008).

Involving Stakeholders

Advising administrators should engage the stakeholder groups at various levels within the planning and assessment cycle. As Figure 1 suggests, the closer stakeholders are to the core, the more direct involvement is required of the group. An advising administrator must facilitate communication and cooperation among the core stakeholders. However, the advising administrator should consider maintaining an active advisee caseload to work directly with students, understand the advising experience at the campus, and keep a finger on the pulse of student needs (Davis, 2008, p. 443).

Additionally, the advising administrator is responsible for facilitating communication and maintaining relationships with Internal but Indirect Stakeholders. Regular contact e.g., annual discussions regarding mutual long-term goals and the sharing of successes, improvements, and impacts, is necessary for keeping these stakeholders engaged and aware of advising goals. This information sharing is beneficial in institutional planning as well as in the promotion of advising to prospective students. Conversely, the advising administrator should also be considered in institutional curriculum and instruction decisions or changes. As Vowell (2008) stated, collaboration across the campus is necessary to provide the most current and accessible information both from advisors and from the institution, information which creates the foundation upon which to build student learning (p. 424).

Of all stakeholder groups, external indirect stakeholders will vary the most between institutions. Advising administrators should stay connected to these groups informing and engaging these various bodies. In some cases these stakeholders, e.g., accrediting bodies, may provide guidance for the continued improvement and design of the advising system.

Allies for Advising

Identifying stakeholders is just one step advising administrators should take when considering the role of advising on campus. Recognizing the strongest allies across stakeholder groups is the second step, although this step is again specific to each institution. The Core Stakeholder group and the Internal Stakeholders should be protagonists for the advising program, but readers should not take generalizations for granted. Policies such as faculty workload, incentives for advising, and advising model can have an impact on how faculty and students view and value an advising program.

Institutional long-term strategic planning – and the departments contributing to that plan – influences the administration of advising. Institutional administrators have an obligation to see that the institution grows in the most appropriate and responsible direction. It can be challenging to argue for professional staff resources over faculty resources, for instance, if an institution places a heavier interest in research and graduate programs. Therefore, advising administrators must align their program directly with the institution’s mission and vision, know their allies, and secure community buy-in for the advising vision and goals if continued success is to be achieved.

What’s Next

Each institution’s stakeholder diagrams will – and should – look slightly different. Environments that are alike in theory may vary greatly in practice. A thoughtful exercise in identifying the institutional stakeholder groups can help draw boundaries for administrators and better define the role of advising in institutional decisions.

While this article refers to the central advising administrator as providing leadership and forging needed connections, readers should remember that advising does not successfully occur in a vacuum. Core stakeholders should be included from across the institution. Responsibility for making and keeping these contacts does not solely rest with the advising administrator. Instead, every member of the institution has the potential to champion collaboration. The process of identifying stakeholders can be a useful step in advocating for a new advising model, requesting additional resources, or in demonstrating the central role of advising to the student learning environment.

Authored by:

Julianne Messia

Academic Support Coordinator, Office of Student Affairs

Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (NY)

References:

Davis, K. (2008). Advising Administrator Perspectives on Advising: Four-Year Public. In V. Gordon, W. Habley, and T. Grites (Eds.) Academic advising: A Comprehensive handbook (2nd edition), (pp. 438-444). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Harney, J. Y. (2008). Campus administrator perspectives on advising: Chief student affairs officer – two-year public. In V. Gordon, W. Habley, and T. Grites (Eds.) Academic advising: A Comprehensive handbook (2nd edition), (pp. 424-430). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Robbins, R. L. (2009). Advising and the campus environment. [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://online.ksu.edu/COMS/player/content/EDCEP_886_CNUTT_1/content/Modules/Module%2012/PPT10-Campus_Env1.ppt%20Module%2012.ppt

Vallandingham, D. (2008). Advising administrator perspectives on advising: Two year colleges. In V. Gordon, W. Habley, and T. Grites (Eds.) Academic advising: A Comprehensive handbook (2nd edition), (pp. 449-454). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Vowell, F. N. (2008). Campus administrator perspectives on advising: Chief academic officer – four-year public. In V. Gordon, W. Habley, and T. Grites (Eds.) Academic advising: A Comprehensive handbook (2nd edition), (pp. 420-424). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cite this using APA style as:

Messia, J. (2010). Defining advising stakeholder groups. Retrieved from NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources Web site:

http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Defining-Advising-Stakeholder-Groups.aspx